Political Strategy In 1900 the United States was planning for a Nicaraguan canal. Meanwhile, the French were desperate to sell their Panama Canal Zone rights to the U.S. for $109,000,000. The U.S deemed the price too high and continued with their decision for a Nicaraguan canal. Supposedly, just prior to the U.S. House ruling in favor of a Nicaraguan Canal, French lobbyist named Phillipe Bunua-Varilla mailed a Nicaraguan stamp depicting the eruption of Momotombo volcano spewing lava and smoke to each undecided U.S. senator. The House ruled in favor of Panama. The French offered the zone, and all rights and equipment for $40,000,000. The U.S. accepted the offer.

Political Strategy In 1900 the United States was planning for a Nicaraguan canal. Meanwhile, the French were desperate to sell their Panama Canal Zone rights to the U.S. for $109,000,000. The U.S deemed the price too high and continued with their decision for a Nicaraguan canal. Supposedly, just prior to the U.S. House ruling in favor of a Nicaraguan Canal, French lobbyist named Phillipe Bunua-Varilla mailed a Nicaraguan stamp depicting the eruption of Momotombo volcano spewing lava and smoke to each undecided U.S. senator. The House ruled in favor of Panama. The French offered the zone, and all rights and equipment for $40,000,000. The U.S. accepted the offer.

Colombia immediately created obstacles for the U.S. therefore the first order of business was to back Panama in becoming its own nation. President Theodore Roosevelt seized the opportunity to support a Panamanian revolt. Colombia, discouraged by the arrival of the U.S. warship Nashville, withdrew forces and within 24 hours Panama declared independence without any bloodshed. On November 3, 1903 the U.S. recognized the new nation and three days later Panama’s ambassador granted full control of the Canal Zone to the U.S.

"Make the Dirt Fly" Between 1904 and 1914 construction of the Panama Canal fell under three different chief engineers: John F. Wallace, John F. Stevens and Colonel George Washington Goethals. Wallace lasted one year until the stress and toil nearly ruined him. John Stevens, engineer of the Great Northern Railroad, was then hired by President Roosevelt. Stevens exhibited a no nonsense attitude and a realistic vision. Defying Roosevelt's demands to "make the dirt fly" Stevens ordered all work to cease as soon as he arrived in Panama. He insisted the Panama Railroad be rebuilt and utilized for the canal project and that a lock canal, not a sea-level waterway (which Roosevelt still thought possible), be constructed. Perhaps Stevens’s most important contribution was the support of Colonel William C. Gorgas, who abated yellow fever and malaria.

After two years Stephens resigned. Roosevelt, tired of delays, took a different hiring approach and appointed someone who couldn't resign. He chose Colonel G.W. Goethals, an Army engineer who served until the canal's completion in 1914. Under Goethals the greatest feats of engineering began: damming the violent Chagres River, building a dam at Gatun Lake, and designing the locks.

Rensselaer Engineers Between 1904 and 1914 seven Rensselaer engineers were involved in planning and construction of the canal. Walter Dauchy (Class of 1875) was appointed division engineer on the Culebra section in 1904. Ricardo Arango (Class of 1887), a Panamanian, was an engineer under both the Columbia and Panama governments. In 1904 he was division engineer in Ancon, Panama. Arango remained in Panama and became the chief engineer of the Republic of Panama. William Baucus (Class of 1887) was a civil engineer with the Municipal Engineering Department in Panama from 1904 to 1907, and was appointed consulting engineer for water works and sewerage systems by the Canal Commission. Baucus also contributed his expertise in the construction of the pipelines for the Pedro Miguel locks.

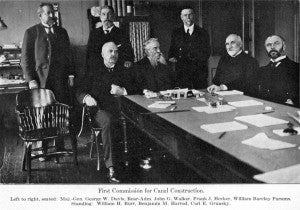

There were three Canal Commissions over the course of U.S. construction and a Rensselaer engineer was on each. William H. Burr (Class of 1872) served on the First Canal Commission appointed by President Roosevelt in 1904. In 1905 Burr was appointed to the International Board of Consulting Engineers to choose what kind of canal would be constructed. In 1905, Rear Admiral Mordecai T. Endicott (Class of 1868) was appointed to the Second Commission. After Endicott resigned, Rear Admiral H.H. Rousseau (Class of 1891) was appointed by Roosevelt to serve on the Third Canal Commission. Under G.W. Goethals, chief engineer of the Panama Canal, Rousseau was appointed as his assistant, a position he held until 1914. Rousseau designed the dry docks, wharves, piers, ship repair shops, coaling plants, fuel plants, breakwaters, and floating cranes.

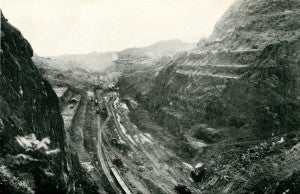

Gatun Lake, the Chagres River, and Culebra Cut A giant dam was created at Gatun Lake to prevent the violent Chagres river from flowing into the sea. At the time the dam was created, it was the largest man-made lake in the world covering 164 square miles of what was once jungle. Between Bas Obispo (the spot where the Chagres flowed down from its source) and Pedro Miguel was the nine-mile stretch of continental divide known as Culebra where the canal had to be “cut” out of the mountains.

Equipment The steam shovels and dredgers employed by the Americans for canal work were famous in their own right. A ninety-five ton Bucyrus steam shovel excavated 4,823 cubic yards of earth and rock in five hours and twenty minutes. Disposing of the earth dredged by the Bucyrus steam shovel was the other battle. For this, the Lidgerwood System was adopted and consisted of trains of flat cars, a plow to sweep the load from the cars, and steel cables reaching the length of the train. Via this system a mass of earth 100 feet wide, 100 feet deep and 50 miles long was removed.

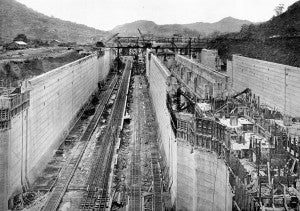

Locks The most remarkable feature of the canal are the six locks. Each has a steel gate with concrete chambers measuring 110’ wide by 1,000’ long. The lock gates themselves measure 7’ thick, 65’ long and 47’ to 82’ high, weighing 300 to 600 tons each.

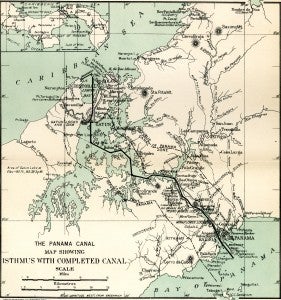

An Engineering Marvel The Panama Canal is 50 miles long. In passing through the canal from the Atlantic to the Pacific, a vessel enters a sea-level channel in Limon Bay (Colon), travels seven miles to Gatun where it enters a series of three locks. The vessel is lifted 85’ above sea level to Gatun Lake where it can travel at full ocean speed for 24 miles. At Bas Obispo it will enter Culebra Cut and travel a distance of 9 miles to reach Pedro Miguel Lock and be lowered 30’ to a small lake, where it sails for about a mile to Miraflores. At Miraflores it enters a series of two locks and is lowered to sea level, passing out to the Pacific 8 ½ miles away. No vessel can enter or pass through the canal under its own power.

It takes approximately nine hours for a ship to pass through the canal. The largest ships that can pass through are called "Panamax." Many modern ships surpass the parameters of Panamax, therefore the canal is currently undergoing the construction of two new sets of locks - one on the Pacific and one on the Atlantic side of the canal. Furthermore, the project includes deepening existing navigational channels in Gatun Lake and Culebra.

In spite of the new construction on the Panama Canal, history comes full circle this year with plans for a Nicaraguan Canal to stretch 173 miles from Punta Gorda on the Caribbean through Lake Nicaragua to the mouth of the River Brito on the Pacific. Engineers for the Hong Kong-based HKND Group said the canal would be between 230m and 520m wide and 27.6m deep. The idea of a Nicaraguan canal is nothing new but unlike the canal A.G. Menocal mapped in the 1870s at a potential cost of $52,000,000, this canal could easily cost about $40 billion!

Before the Panama Canal was built ships, traveling from the Atlantic to the Pacific traveled around the southern tip of South America. The journey was 13,000 miles around Cape Horn from New York to California. The Panama Canal reduces the journey to 5,200 miles. Today, the canal accommodates 14,000 ships a year on average, carrying over 200 million tons of cargo, representing five percent of the world's shipping. The Rensselaer engineers who helped connect the oceans, helped changed the world forever. Today even more Rensselaer engineers continue this legacy with new lock construction in Panama.

This concludes our Panama Canal Centennial Celebration post blitz. Please check out the exhibit in Folsom Library on the 2nd floor.

Comments

Fascinating reading! No surprise that RPI engineers were such an integral part of the Canal's success.

In reply to by egglel

Thank you Tracey!! And the story continues on even after I've finished. I couldn't fit anymore!!!