Upon helping a researcher based in Shelter Island, New York, last month, I had to peruse the Institute Archives’ expansive Horsford collection, which I hadn’t done before. Among fun items, such as colonial currency dated to 1775, an 1839 newspaper story of a young girl becoming a pirate, and a lady throwing a summer party in the Roaring Twenties, where attendees had to dress up as Colonial Quakers, something else caught my eye: wax seals. Sure, out of everything else I’ve listed, that might seem a bit mundane, but what these physical wax seals actually reveal is a story so rich in family drama, it could be its own reality TV series.

While reading through multiple folders of correspondence, particularly from Mary Catherine L’Hommedieu, I began to notice the steady decline in the quality of the wax seals that she used over time. It seemed as though, with each year that passed, the seals got worse and worse, until she wasn’t using wax at all, but cheap paper wafers to help seal her letters together. As the wife of a prominent Shelter Island resident, Ezra L’Hommedieu, who should have been able to afford better quality seals, I couldn’t help but wonder why this was.

Before we get into that, though, let’s quickly go over the history of wax seals. Becoming popular in the Middle Ages, sealing wax was used on most items that were delivered as mail, and the wax seals in particular became a symbol of social standing. Wealthier families used the more expensive, glossy, hard shellac-based wax, sealing them with a coat of arms stamp or a personalized signet ring. As the world became more literate, and middle class families started writing more letters in the 19th century, a cheaper, yet more brittle wax was developed. Though still effective as a seal, the cheaper waxes tended to break, crumble, or even rip portions of the letter apart. The cheapest seals used though were wafer seals; gum-based wafers that the writer would wet under their tongue, and then use a textured stamp to effectively smoosh the paper together, forming the seal. While cheap and plentiful, they were not favored among wealthier families, as the wafers had a tendency to break, obscure writing on the letter itself, or even grow mold. So, how exactly does this relate to Mary Catherine L’Hommedieu?

The Havens sisters, Mary Catherine and Esther Sarah, each married into prominent Shelter Island families, with Esther Sarah marrying Sylvester Dering in 1787, and Mary Catherine marrying Ezra L’Hommedieu in 1803. Ezra passed in 1811, and Sylvester tragically passed in 1820 after a fall from his horse. After his death, it was revealed to Esther Sarah that her husband, Sylvester, owed Ezra almost $8,000, which would be the equivalent to almost $194,000 today. Esther Sarah no longer had the funds to pay her sister, and so…she didn’t, as simple as that. Letters written by the sisters’ lawyers reveal to us that they weren’t aware of the debts either, until Mary Catherine realized that she was losing money at a rapid rate and inquired as to why. What followed was a search for the debt book through Esther Sarah’s house, Mary Catherine cutting off contact with her sister, a feud which lasted until her death, and Esther Sarah’s children being burdened with the debts that they were then made to pay back in installments.

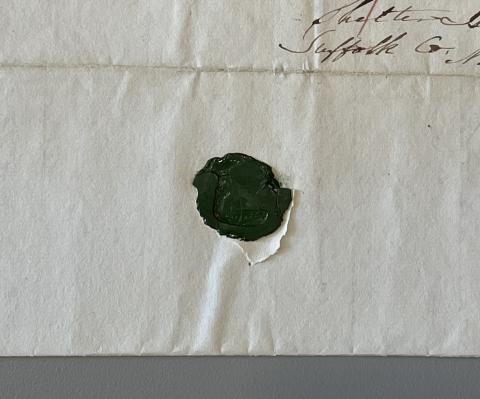

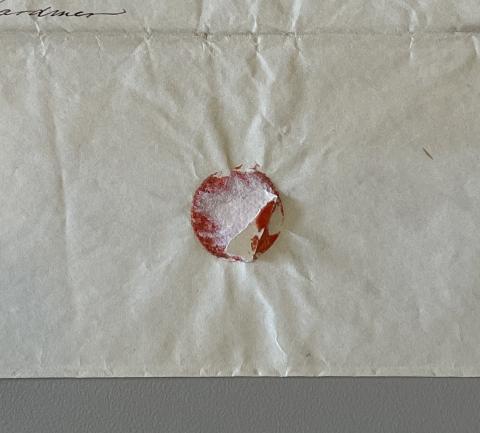

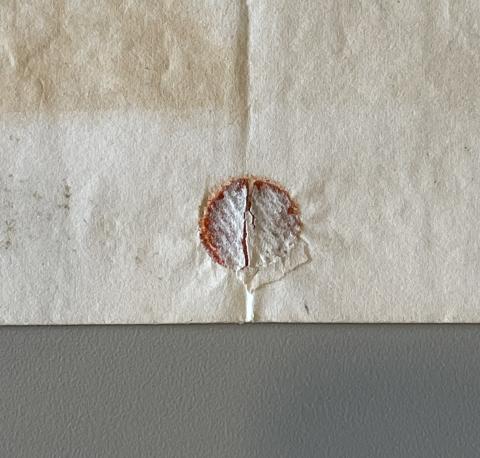

As Mary Catherine’s funds started to dry up, so did the wax seals. Seen throughout this post, on a letter dated from 1812, we can see a dark green, glossy, shellac-based wax seal, used by Mary Catherine. In 1825, on another letter written by Mary Catherine, we’re able to see the cheaper wax that started gracing the pages of her letters. It’s crumbly, broken, and part of the paper is torn. Finally, by 1838, we can see the use of a wafer seal. The tiny, pock-marked indentations are confirmation of the textured stamp used to seal wafers.

Mary Catherine would pass in 1843, leaving her estate to a daughter, and her wax seals to be pored over by a history buff 179 years later. The seals might not be as flashy as a Colonial Quaker party, but even the smallest of details can tell a huge story!