August 15, 2014 marked the 100th anniversary of the Panama Canal - its completion being one of the greatest feats of engineering by mankind, and one which rested on an idea four centuries old! This fact brings to light the amazing contributions of Rensselaer engineers who followed in some pretty hefty footsteps of those eager to connect the oceans. Some played a rather small part, while others rose high above the ranks, and were bestowed with great honor for their achievements. This post is the first in a series that weaves the contributions of our engineers into the indefatigable triumph over nature to build a canal that many people never thought would come to fruition.

August 15, 2014 marked the 100th anniversary of the Panama Canal - its completion being one of the greatest feats of engineering by mankind, and one which rested on an idea four centuries old! This fact brings to light the amazing contributions of Rensselaer engineers who followed in some pretty hefty footsteps of those eager to connect the oceans. Some played a rather small part, while others rose high above the ranks, and were bestowed with great honor for their achievements. This post is the first in a series that weaves the contributions of our engineers into the indefatigable triumph over nature to build a canal that many people never thought would come to fruition.

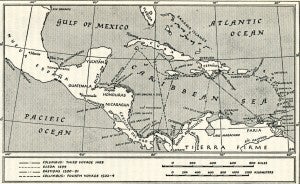

Around 1502 Columbus made his fourth and last voyage to the New World, sailing along the never ending stretch of Central America looking again for a passageway through the Isthmus. In 1513, Vasco Nunez de Balboa gathered a hundred men and set out on an expedition across the Isthmus to find the mighty sea that natives spoke of. Balboa, though on foot, became the first European to observe what we now know as the Pacific Ocean. Since this time men have been eager for a passageway.

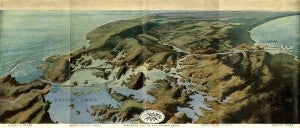

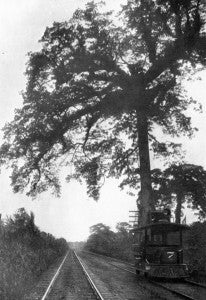

Not until the 1800s did men seriously consider carving a path across the Isthmus to connect the oceans. Numerous surveys were conducted across Mexico, Nicaragua, and Panama primarily by the United States government but also by the French and British. Nevertheless, the first colossal endeavor that made the oceans meet was the Panama Railroad, backed by New York financiers and completed in 1855 accommodating those eager to reach California for new found gold. The railroad satisfied many needs, but a water route was always the ultimate goal. Here we give praise to Gilbert T. Taylor (RPI 1844). Though we know little about his career we've discovered he was a general freight agent on the Panama Railroad throughout the 1850s.

Three places were considered for a water route, one across the Isthmus of Tehuentepec in Mexico, another option was across the Isthmus in Nicaragua, and another, across the Isthmus of Panama. We are pleased to also discover that Frederico Garcia y Garcia (RPI 1872), was sent by the government of Peru in 1873 to verify one particular survey by Commander Thomas Oliver Selfridge for an inter-oceanic canal route on the Isthmus of Panama.

Other RPI engineers placed their mark on this part of history too, handing us quite a legacy!

In 1870 President Ulysses S. Grant named Estevan Fuertes (RPI 1861) Chief Engineer in charge of studying a potential water route via Tehuantepec in Mexico to connect the oceans. The report that Fuertes wrote is one of the most valuable documents that exists regarding this potential passageway through Tehuantepec.

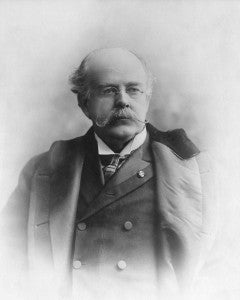

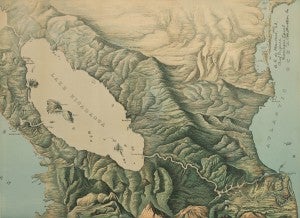

In 1872 President Grant then placed Aniceto Garcia Menocal (RPI 1862) in charge of mapping a route across Nicaragua. In 1875, another team from the U.S. surveyed Panama -- then a part of the Republic of Colombia -- for a feasible canal route. Nevertheless, Menocal remained a staunch advocate for the Nicaraguan Canal arguing that it possessed lower mountain passes and existing usable lakes and that a canal placed there would lie closer to American ports than one built across Panama. Menocal was invited to France in 1880 and was one of only a few American delegates invited to speak at the Congres International d’Etudes du Canal Interoceanic. While there, he stood up against Ferdinand de Lesseps, the "Great Engineer" responsible for the Suez Canal in 1869, opposing de Lesseps proposition for a sea-level waterway through the isthmus.

In 1869 President Grant insisted upon "an American canal under American control." He regarded a canal across the isthmus of the utmost importance to the political positioning of the United States but the French prevailed!

Stay tuned for next week's post regarding the French Debacle...